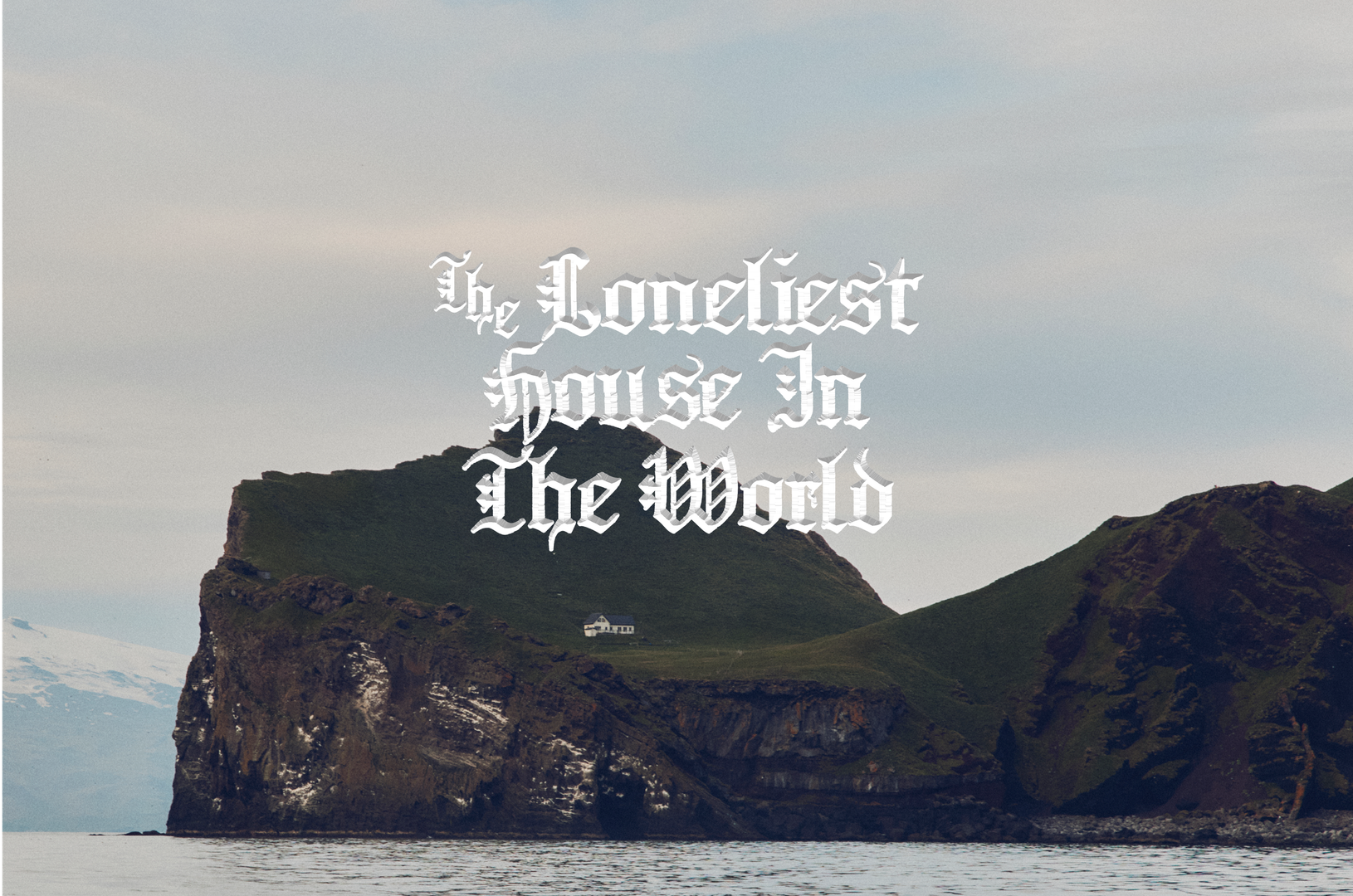

The Loneliest House In The World

There are very few golf trips on which you run the risk of getting caught between a cliff face and the bow of a boat. A wave comes through, knocking me off balance, and Elvis Presley runs the length of our vessel and leaps three feet high onto the slippery rock above, looking more mountain goat than French bulldog.

Every year, Ragnarthor gets thousands of people asking if they can visit his island and he issues thousands of rejections. We are one of just two groups allowed onto the island, precisely because we asked if we might do something stupid. Something we think will look really, really cool.

“AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAHHHHHHHHHH!” bellows Ragnarthor like the Norse gods he’s named after.

Sat in the palm of the gnarled green hand that is Ellidaey Island is a white house with a sloped metal roof and a huge New England–style porch. The view overlooking the Vestmannaeyjar is a privilege very few have seen.

Inside, the atmosphere isn’t far off an old clubhouse like Royal Porthcawl or Western Gailes. The room is made from rich, warm pine that smells freshly cut. Past legends of the hunting association adorn the walls, and their trophy birds hang from the ceiling. A bottle of cognac hangs with 6 glasses and we all partake. Upstairs, is lodging for at least 20 people.

Raggi and the other hunters guard Ellidaey’s secrets carefully, partly because they’re controversial in the modern context. Chief among them is puffin hunting. To many foreigners, the idea of hunting and eating puffin, like whaling, sits uncomfortably, given the bird’s vulnerable status. But for the 40 or so members of the hunting association, the tradition is rooted in pride and responsibility. They see themselves not as the problem, but as guardians of the island’s delicate ecosystem. Their methods are small-scale, seasonal, and deeply respectful of the land. In their view, the real threat to puffins lies in warming seas, vanishing fish stocks, and habitat loss, not in the few hands skilled enough to catch one.

After hotdogs and beers, we decide it’s time for the main event. Raggi chuckles. For better or worse, he’d rather a group of idiots show up with a bold idea and have a laugh than host a stiff, well-meaning documentarian. He’s more comfortable with a bit of chaos than with influencers or journalists trying to extract something profound from his house on the edge of the world.

Up his mountain we go, climbing for the peak in full golfwear, bags slung over shoulders, eyes pinned upwards. The nesting puffins in the rocks make it sound as if the cliffs are groaning under our weight—which is unnerving, given the incline and steep fall on the other side.

We reach the top of the 99 Flake–shaped cliff and look out over the sharp drop on the far side. Jake shouts in triumph. The puffins take off. That’s what we came for.

Raggi grins as we get to the bottom. The fact that he delivered is written all over our faces.

“You know, one day those cliffs you were on will fall into the ocean.”